Populations: Practicals#

This section contains practical work exercises related to single population modelling.

# Core imports

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from math import log, exp

(1-1) Exponential Growth Model#

Model#

Continuous-time exponential growth:

Doubling time:

Problem (1-1)#

In year 600, human population: 200 million. In year 1300: 360 million.

Calculate the per-capita growth rate \(r\) (per year), assuming exponential growth.

Calculate doubling time.

In year 1000: 265 million. In year 1200: 360 million.

Assume exponential growth continues at the same rate. Predict population in 1975.

In year 1750: 720 million. In year 1850: 1200 million.

Compute doubling time for this period and compare. Is constant \(r\) reasonable?

# (1-1) Calculations

# Part 1: 600 -> 1300

N600 = 200 # million

N1300 = 360 # million

dt_600_1300 = 1300 - 600 # years

r_600_1300 = (log(N1300/N600)) / dt_600_1300

Td_600_1300 = log(2) / r_600_1300

r_600_1300, Td_600_1300

(0.0008396952355744558, 825.4747093875632)

Solution (600 → 1300):

We solve

Then

print(f"Per-capita growth rate r (600→1300): {r_600_1300:.6f} per year (~{100*r_600_1300:.3f}%/yr)")

print(f"Doubling time Td (600→1300): {Td_600_1300:.1f} years")

Per-capita growth rate r (600→1300): 0.000840 per year (~0.084%/yr)

Doubling time Td (600→1300): 825.5 years

# Part 2: 1000 -> 1200; forecast to 1975

N1000 = 265 # million

N1200 = 360 # million

dt_1000_1200 = 1200 - 1000 # years

r_1000_1200 = (log(N1200/N1000)) / dt_1000_1200

# forecast 1200 -> 1975

dt_1200_1975 = 1975 - 1200

N1975_pred = N1200 * exp(r_1000_1200 * dt_1200_1975)

r_1000_1200, N1975_pred

(0.0015318710273196671, 1180.0405456891353)

Forecast (1000 → 1200 rate continued to 1975):

print(f"Per-capita growth rate r (1000→1200): {r_1000_1200:.6f} per year (~{100*r_1000_1200:.3f}%/yr)")

print(f"Predicted population in 1975 (if 1000→1200 rate held): {N1975_pred:.1f} million ({N1975_pred/1000:.2f} billion)")

Per-capita growth rate r (1000→1200): 0.001532 per year (~0.153%/yr)

Predicted population in 1975 (if 1000→1200 rate held): 1180.0 million (1.18 billion)

Reality check: Actual 1975 population ≈ 3900 million (3.9 billion), so the medieval-calibrated exponential model underestimates late-20th-century growth, implying a strong increase in effective growth rates over time.

# Part 3: 1750 -> 1850

N1750 = 720 # million

N1850 = 1200 # million

dt_1750_1850 = 1850 - 1750

r_1750_1850 = (log(N1850/N1750)) / dt_1750_1850

Td_1750_1850 = log(2) / r_1750_1850

print(f"Per-capita growth rate r (1750→1850): {r_1750_1850:.6f} per year (~{100*r_1750_1850:.3f}%/yr)")

print(f"Doubling time Td (1750→1850): {Td_1750_1850:.1f} years")

Per-capita growth rate r (1750→1850): 0.005108 per year (~0.511%/yr)

Doubling time Td (1750→1850): 135.7 years

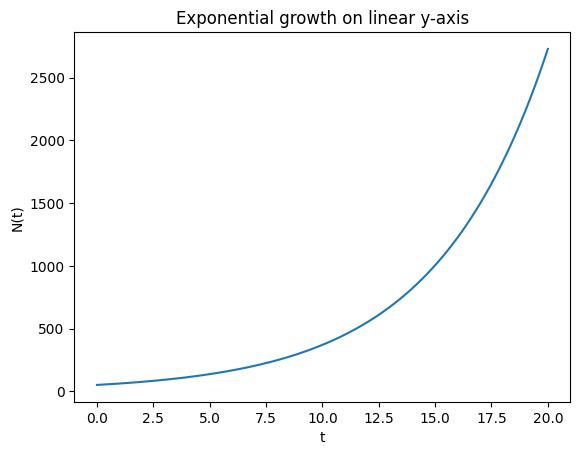

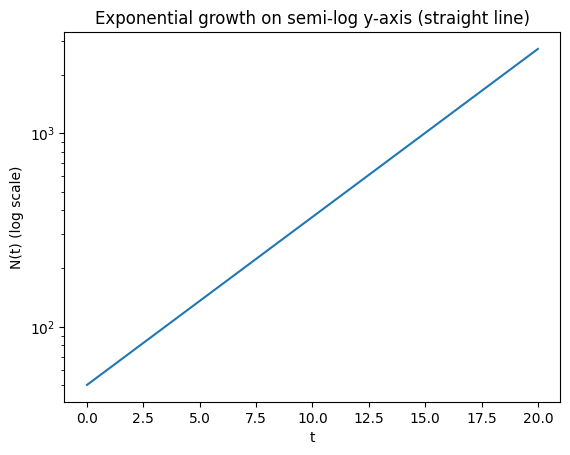

Semi-log straight-line property*#

Show that exponential growth is linear in semi-log coordinates:

If \(N(t)=N_0e^{rt}\), then

which is a straight line with slope \(r\) and intercept \(\ln N_0\).

We verify this numerically and with a plot.

# Semi-log demonstration

N0 = 50

r = 0.2

t = np.linspace(0, 20, 200)

N = N0 * np.exp(r*t)

plt.figure()

plt.plot(t, N)

plt.xlabel("t")

plt.ylabel("N(t)")

plt.title("Exponential growth on linear y-axis")

plt.show()

plt.figure()

plt.semilogy(t, N)

plt.xlabel("t")

plt.ylabel("N(t) (log scale)")

plt.title("Exponential growth on semi-log y-axis (straight line)")

plt.show()

# Check linearity of ln(N) vs t

coef = np.polyfit(t, np.log(N), 1)

print("Fitted slope, intercept for ln(N) = intercept + slope*t:", coef[0], coef[1])

Fitted slope, intercept for ln(N) = intercept + slope*t: 0.20000000000000004 3.912023005428146

Fibonacci rabbits & Golden Ratio*#

Classic Fibonacci recurrence:

Try \(F_n\sim \lambda^n\), giving

The dominant growth factor is the Golden Ratio

We compute ratios \(F_{n+1}/F_n\) to see convergence to \(\phi\).

# Fibonacci ratios converge to golden ratio

fib = [1, 1]

for i in range(2, 25):

fib.append(fib[i-1] + fib[i-2])

ratios = [fib[i+1]/fib[i] for i in range(5, 20)]

print("Selected ratios F[n+1]/F[n]:")

for i, val in enumerate(ratios, start=6):

print(f"n={i}: {val:.6f}")

phi = (1 + 5**0.5)/2

print("Golden ratio phi:", phi)

Selected ratios F[n+1]/F[n]:

n=6: 1.625000

n=7: 1.615385

n=8: 1.619048

n=9: 1.617647

n=10: 1.618182

n=11: 1.617978

n=12: 1.618056

n=13: 1.618026

n=14: 1.618037

n=15: 1.618033

n=16: 1.618034

n=17: 1.618034

n=18: 1.618034

n=19: 1.618034

n=20: 1.618034

Golden ratio phi: 1.618033988749895

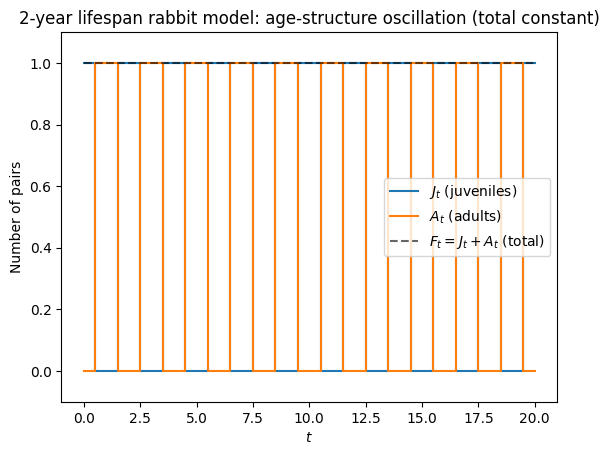

Fibonacci rabbits die after their second year*#

One simple way to model a 2-year lifespan is with two classes:

\(J_t\): juveniles (non-reproductive)

\(A_t\): adults (reproductive, die after reproducing)

Assuming each adult produces one new juvenile each time step and adults do not survive to the next time step:

This gives the matrix model

Eigenvalues are \(\pm 1\) so the dominant growth factor is 1: no long-term growth. However, the age structure oscillates: juveniles and adults alternate each time step (a 2-cycle).

We simulate to illustrate this.

# Simulate the 2-year lifespan rabbit model

T = 20

J = np.zeros(T+1)

A = np.zeros(T+1)

# start with one juvenile pair

J[0] = 1

A[0] = 0

for t_ in range(T):

# adults at time t_ reproduce (one juvenile) then die

J[t_+1] = A[t_]

# juveniles mature into adults

A[t_+1] = J[t_]

F = J + A

plt.figure()

plt.step(range(T+1), J, where='mid', label=r'$J_t$ (juveniles)')

plt.step(range(T+1), A, where='mid', label=r'$A_t$ (adults)')

plt.step(range(T+1), F, where='mid', linestyle='--', color='k', alpha=0.6, label=r'$F_t=J_t+A_t$ (total)')

plt.xlabel(r'$t$')

plt.ylabel('Number of pairs')

plt.title('2-year lifespan rabbit model: age-structure oscillation (total constant)')

plt.ylim(-0.1, 1.1)

plt.legend()

plt.show()

# Show the oscillation explicitly

list(zip(J[:10].astype(int).tolist(), A[:10].astype(int).tolist(), F[:10].astype(int).tolist()))

[(1, 0, 1),

(0, 1, 1),

(1, 0, 1),

(0, 1, 1),

(1, 0, 1),

(0, 1, 1),

(1, 0, 1),

(0, 1, 1),

(1, 0, 1),

(0, 1, 1)]

(1-2) Continuous Logistic Equation — Bifurcation Diagram#

Model#

with parameters \(r\) and \(K\) (carrying capacity).

Equilibria solve \(0 = r n (K-n)\Rightarrow n^*=0\) or \(n^*=K\).

Problem (1-2)#

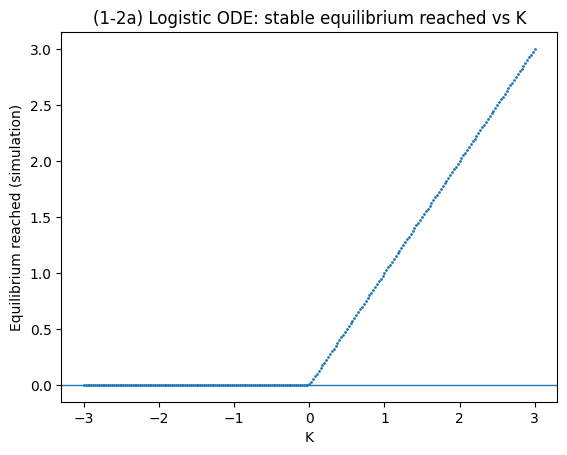

(a) Simulate the ODE with \(r=1\) while stepping \(K\) from 3 to -3, recording the stable equilibrium reached.

(b) Numerically find equilibria by root-finding for \(0 = r n (K-n)\) using continuation:

start near \(n\approx K\) to track the \(n=K\) branch,

start near \(n\approx 0\) to track the \(n=0\) branch.

(c) Linearize and identify stable vs unstable branches.

# We'll use scipy for numerical integration & root finding

from scipy.integrate import solve_ivp

from scipy.optimize import root

def logistic_rhs(t, n, r, K):

return r*n*(K - n)

# (a) Simulate and record stable equilibrium

r = 1.0

Ks = np.linspace(3, -3, 241) # step from 3 down to -3

stable_eq = []

n0 = 0.1 # non-zero initial condition

t_span = (0, 50)

t_eval = np.linspace(t_span[0], t_span[1], 2000)

for K in Ks:

sol = solve_ivp(logistic_rhs, t_span, [n0], t_eval=t_eval, args=(r, K), rtol=1e-8, atol=1e-10)

n_end = sol.y[0, -1]

stable_eq.append(n_end)

# continuation in IC helps convergence

n0 = max(n_end, 1e-8)

stable_eq = np.array(stable_eq)

plt.figure()

plt.plot(Ks, stable_eq, marker='.', linestyle='none', markersize=2)

plt.axhline(0, linewidth=1)

plt.xlabel("K")

plt.ylabel("Equilibrium reached (simulation)")

plt.title("(1-2a) Logistic ODE: stable equilibrium reached vs K")

plt.show()

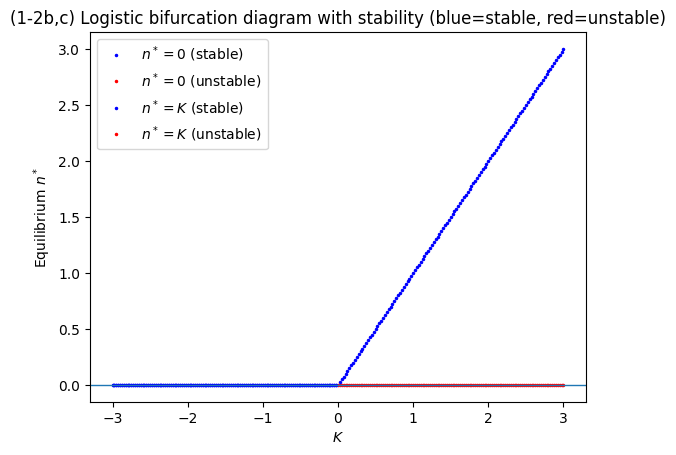

(1-2b) Root-finding / continuation for both equilibrium branches#

Equilibria satisfy \(f(n) = r n (K-n) = 0\).

We numerically track solutions as \(K\) decreases:

Start with an initial guess near \(n\approx K\) to follow the \(n=K\) branch

Start with an initial guess near \(n\approx 0\) to follow the \(n=0\) branch

def equilibrium_root(K, guess, r=1.0):

f = lambda n: r*n*(K - n)

sol = root(lambda x: f(x[0]), x0=np.array([guess]))

return sol.x[0], sol.success

Ks2 = np.linspace(3, -3, 241)

# Track n=K branch

eq_K = []

guess = 3.0

for K in Ks2:

val, ok = equilibrium_root(K, guess, r=r)

eq_K.append(val if ok else np.nan)

guess = val

# Track n=0 branch

eq_0 = []

guess = 1e-6

for K in Ks2:

val, ok = equilibrium_root(K, guess, r=r)

eq_0.append(val if ok else np.nan)

guess = val

eq_K = np.array(eq_K)

eq_0 = np.array(eq_0)

# Stability by linearization: f'(n)=r(K-2n)

def stability(K, n, r=1.0):

fp = r*(K - 2*n)

return fp < 0 # stable if derivative negative

stable_K = np.array([stability(K, n, r=r) for K, n in zip(Ks2, eq_K)])

stable_0 = np.array([stability(K, n, r=r) for K, n in zip(Ks2, eq_0)])

plt.figure()

# plot branches with stability styling

plt.plot(Ks2[stable_0], eq_0[stable_0], 'b.', markersize=3, label=r'$n^*=0$ (stable)')

plt.plot(Ks2[~stable_0], eq_0[~stable_0], 'r.', markersize=3, label=r'$n^*=0$ (unstable)')

plt.plot(Ks2[stable_K], eq_K[stable_K], 'b.', markersize=3, label=r'$n^*=K$ (stable)')

plt.plot(Ks2[~stable_K], eq_K[~stable_K], 'r.', markersize=3, label=r'$n^*=K$ (unstable)')

plt.axhline(0, linewidth=1)

plt.xlabel(r'$K$')

plt.ylabel(r'Equilibrium $n^*$')

plt.title("(1-2b,c) Logistic bifurcation diagram with stability (blue=stable, red=unstable)")

plt.legend()

plt.show()

(1-2c) Linearization and stability#

Let \(f(n)=r n (K-n)\). Then

At \(n^*=0\): \(f'(0)=rK\) so stable if \(K<0\), unstable if \(K>0\).

At \(n^*=K\): \(f'(K)=r(K-2K)=-rK\) so stable if \(K>0\), unstable if \(K<0\).

This is a transcritical bifurcation at \(K=0\).

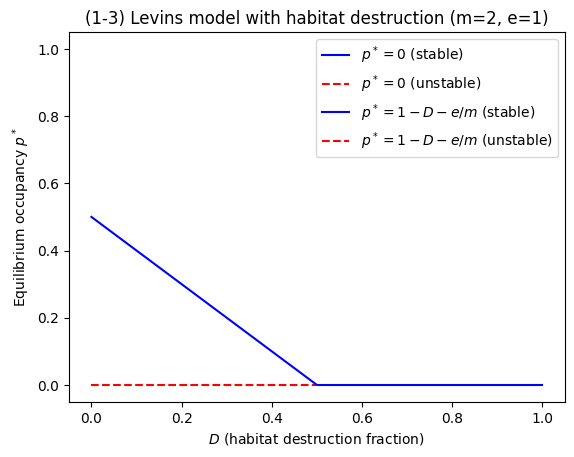

(1-3) Levins’ Metapopulation Model with Habitat Destruction#

Model#

Here \(p\) is fraction of patches occupied, \(m\) colonization rate, \(e\) extinction rate, and \(D\) fraction destroyed (unavailable).

Problem (1-3)#

Find equilibria and determine stability.

Plot equilibrium solutions as a function of \(D\) using numerical root-finding (as in 1-2).

def levins_destroy_rhs(p, m, e, D):

return m*p*(1 - D - p) - e*p

# Analytic equilibria:

# p*=0 and p*=1-D-e/m (when positive)

# We'll demonstrate with specific parameter choices and plot branches

m = 2.0

e = 1.0

Ds = np.linspace(0, 1, 501)

p0 = np.zeros_like(Ds)

p_pos = 1 - Ds - e/m # may be negative

# Stability: f'(p)=d/dp[m p(1-D-p)-e p] = m(1-D-2p)-e

def levins_destroy_stable(p, m, e, D):

fp = m*(1 - D - 2*p) - e

return fp < 0

stable_p0 = np.array([levins_destroy_stable(0.0, m, e, D) for D in Ds])

stable_pp = np.array([levins_destroy_stable(p, m, e, D) if np.isfinite(p) else False for p, D in zip(p_pos, Ds)])

plt.figure()

# p=0 branch

plt.plot(Ds[stable_p0], p0[stable_p0], 'b-', label=r'$p^*=0$ (stable)')

plt.plot(Ds[~stable_p0], p0[~stable_p0], 'r--', label=r'$p^*=0$ (unstable)')

# positive branch

mask_exists = p_pos >= 0

plt.plot(Ds[mask_exists & stable_pp], p_pos[mask_exists & stable_pp], 'b-', label=r'$p^*=1-D-e/m$ (stable)')

plt.plot(Ds[mask_exists & ~stable_pp], p_pos[mask_exists & ~stable_pp], 'r--', label=r'$p^*=1-D-e/m$ (unstable)')

plt.xlabel(r'$D$ (habitat destruction fraction)')

plt.ylabel(r'Equilibrium occupancy $p^*$')

plt.title("(1-3) Levins model with habitat destruction (m=2, e=1)")

plt.ylim(-0.05, 1.05)

plt.legend()

plt.show()

Dcrit = 1 - e/m

print("Critical destruction threshold Dcrit = 1 - e/m =", Dcrit)

Critical destruction threshold Dcrit = 1 - e/m = 0.5

Analytical solution & stability#

Equilibria from \(0 = m p(1-D-p) - e p = p[m(1-D-p)-e]\):

\(p^*=0\)

\(p^*=1-D-\frac{e}{m}\) (exists as a biologically meaningful equilibrium only if \(p^*>0\), i.e. \(m(1-D) > e\)).

Stability from derivative:

At \(p^*=0\): stable if \(m(1-D)-e<0\) (i.e. \(D>1-e/m\))

At \(p^*=1-D-e/m\): stable whenever it exists (\(m(1-D)>e\))

Thus the system shows a transcritical bifurcation at

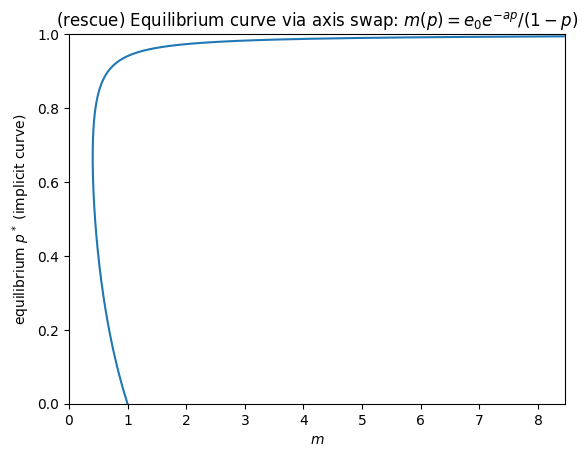

(1-3) Levins’ Metapopulation Model with Rescue Effect#

Model#

Problem (1-3, rescue effect)#

Can you solve for equilibrium with pen & paper? Why is it difficult?

Plot equilibria as a function of \(m\) (hint: swap x and y axes).

Determine stability and interpret the bifurcation structure. Compare to the case \(a=0\).

We’ll:

Use the implicit equilibrium condition for \(p>0\):

Plot \(m\) vs \(p\) (axis swap), then invert mentally to see \(p\) vs \(m\).

Compute stability using linearization \(f'(p)\).

def levins_rescue_rhs(p, m, e0, a):

return m*p*(1 - p) - e0*p*np.exp(-a*p)

def levins_rescue_fp(p, m, e0, a):

# derivative wrt p of RHS

# f(p) = m p (1-p) - e0 p exp(-a p)

# f'(p) = m(1-2p) - e0[exp(-ap) + p(-a)exp(-ap)]

return m*(1 - 2*p) - e0*(np.exp(-a*p) - a*p*np.exp(-a*p))

# Parameters given in sheet (use e0=1, a=3, explore m)

e0 = 1.0

a = 3.0

# Axis-swap curve: m(p) for p in (0,1)

p_grid = np.linspace(1e-4, 0.999, 2000)

m_curve = (e0*np.exp(-a*p_grid)) / (1 - p_grid)

plt.figure()

plt.plot(m_curve, p_grid)

plt.xlabel(r'$m$')

plt.ylabel(r'equilibrium $p^*$ (implicit curve)')

plt.title(r"(rescue) Equilibrium curve via axis swap: $m(p)=e_0 e^{-a p}/(1-p)$")

plt.xlim(0, np.percentile(m_curve, 99.5))

plt.ylim(0, 1)

plt.show()

# Find saddle-node (minimum of m(p))

idx = np.argmin(m_curve)

print("Approx saddle-node at:")

print("p ~", p_grid[idx], "m ~", m_curve[idx])

Approx saddle-node at:

p ~ 0.6666995997998999 m ~ 0.4060058516915454

Why solving analytically is difficult#

Equilibria satisfy, for \(p>0\):

The unknown \(p\) appears both in a polynomial term \((1-p)\) and inside an exponential \(e^{-ap}\), giving a transcendental equation. There is no elementary closed-form solution for \(p(m)\) in general (it can be expressed using special functions in some rearrangements, but the practical approach is numerical).

Finding stable vs unstable branches#

We can find equilibria for each \(m\) using root finding with continuation (like earlier), using multiple initial guesses to capture multiple branches. We’ll scan \(m\) over a range and collect roots found from different starting guesses, then assess stability from \(f'(p^*)<0\).

from collections import defaultdict

def find_equilibria_for_m(m, e0, a, guesses):

roots = []

for g in guesses:

sol = root(lambda x: levins_rescue_rhs(x[0], m, e0, a), x0=np.array([g]))

if sol.success:

p = sol.x[0]

# keep within [0,1] with tolerance

if -1e-6 <= p <= 1+1e-6:

p = min(max(p, 0.0), 1.0)

roots.append(p)

# deduplicate

roots_sorted = sorted(roots)

uniq = []

for p in roots_sorted:

if not uniq or abs(p - uniq[-1]) > 1e-3:

uniq.append(p)

return uniq

ms = np.linspace(0.0, 2.0, 401)

guesses = [0.0, 1e-4, 0.05, 0.2, 0.5, 0.8, 0.95]

all_roots = []

all_m = []

all_stable = []

for m in ms:

roots = find_equilibria_for_m(m, e0, a, guesses)

for p in roots:

fp = levins_rescue_fp(p, m, e0, a)

stable = fp < 0

all_m.append(m)

all_roots.append(p)

all_stable.append(stable)

all_m = np.array(all_m)

all_roots = np.array(all_roots)

all_stable = np.array(all_stable)

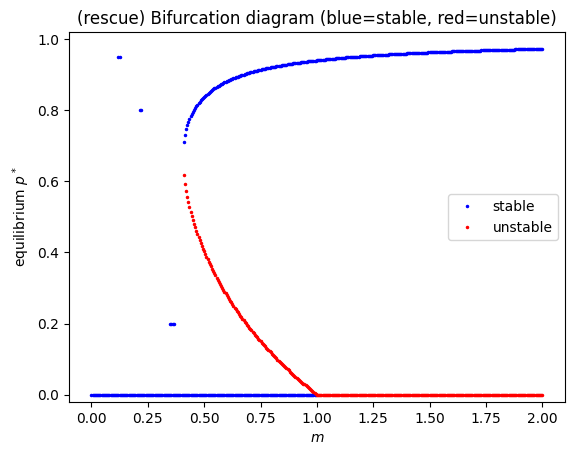

plt.figure()

plt.plot(all_m[all_stable], all_roots[all_stable], 'b.', markersize=3, label='stable')

plt.plot(all_m[~all_stable], all_roots[~all_stable], 'r.', markersize=3, label='unstable')

plt.xlabel(r'$m$')

plt.ylabel(r'equilibrium $p^*$')

plt.title("(rescue) Bifurcation diagram (blue=stable, red=unstable)")

plt.ylim(-0.02, 1.02)

plt.legend()

plt.show()

# Note: p=0 stability threshold is m=e0

print("p=0 changes stability at m=e0 =", e0)

p=0 changes stability at m=e0 = 1.0

Interpreting the rescue-effect bifurcation#

The axis-swap curve \(m(p)=\frac{e_0 e^{-ap}}{1-p}\) typically has a minimum for \(a>0\).

That minimum corresponds to a saddle-node bifurcation, where two equilibria (one stable, one unstable) appear.

Separately, \(p=0\) changes stability at \(m=e_0\) because:

\[ f'(0)=m-e_0. \]When \(a=0\), \(e_0 e^{-ap}=e_0\) is constant and the model reduces to classic Levins:

\[ \frac{dp}{dt}=mp(1-p)-e_0 p, \]which has only a transcritical bifurcation at \(m=e_0\) and no saddle-node.

The unstable branch is the “missing branch” if you only track stable solutions by simulation.